In modern digital infrastructure, containerization has become one of the most significant technologies, offering automation, portability, and resilience of services across cloud and on-premises environments. Containers can simplify backup processes and enhance upgrade safety while significantly reducing recovery times following system incidents or failed updates.

This article provides an overview of the container technology and focuses on Podman, a modern, daemonless container engine. Podman serves as the primary, Red Hat supported container solution in Red Hat Enterprise Linux and is widely available across major Linux distributions such as Fedora, Debian, Ubuntu, Arch, and SUSE.

Podman offers several features, including the ability to run containers without requiring root permissions on the host. This article will explore Podman’s security benefits, how it technically differs from other popular container engines such as Docker and practical ways it can be used to harden a company’s infrastructure built on it.

Overview of Containers and Their Security Implications

Containers represent a complete runtime environment for applications, packaging code, libraries, settings, and other userland dependencies into isolated “boxes” that behave consistently across different platforms while sharing the host’s kernel rather than running their own.

This isolation reduces the risk of system-wide dependency conflicts and simplifies deployment pipelines.

By using a simple YAML file to define multiple containers, system administrators can design and manage their own services and maintain them securely, making backups and migrations easier as the application data typically resides in volumes or external storage (such as databases or object storage) that can be backed up independently of the container images reliably.

For example, a container can “contain” an operating system (but uses the host’s kernel), a service (e.g. a web server), a database, or even an entire application.

#Template of a Compose YAML file for both Podman and Docker with nginx web server

web:

image: nginx:alpine

ports:

- "8080:80"

volumes:

- ./html:/usr/share/nginx/html:ZTraditional GNU/Linux software installation often includes manual dependency management which can lead to broken applications after system upgrades. Many newer software versions require specific library versions and other dependencies, making updates more difficult. As a result, many companies run older legacy servers with outdated operating systems, increasing their attack surface.

Containers mitigate these side-effects by segregating the application’s environment from unintended external factors or dependencies. The designed segregation enables operators to manage the desired state (apply or roll-back updates), thus improving company’s patch management while reducing the overall risk posture.

Core Container Architecture

As discussed previously, containers are built from images that package everything needed to run applications, such as web servers, Linux distributions, or databases. Key components of container architecture include:

- Image download and verification processes, to ensure integrity,

- Storage volumes, mapped to host directories for persistent data storage,

- Network port bindings that enable controlled communication between containers and external systems,

- Assignment to dedicated virtual networks for segmentation and isolation,

- Unique container identifiers used for policy enforcement, monitoring, and auditing purposes,

- Optional resource limiting features that help manage container resource usage and ensure host system stability.

As containers use images containing everything needed and volumes store application data separately, this approach helps system administrators back up volumes and move them to other systems with reduced downtime, easing migrations, especially when the applications and the orchestration are designed to support such changes.

If an image supports multiple architectures (such as x86_64 and ARM), pairing the volume with the correct architecture-specific image ensures the service remains fully functional. This allows services to run smoothly across different hardware platforms without compatibility problems.

Administrators can dynamically reconfigure container networking, increase storage by attaching new volumes, and upgrade by replacing images, supporting effective vulnerability and lifecycle management.

Disk Management and Backups

For instance, if a container runs out of space, an administrator can provision and attach additional storage as a new volume and then migrate data with minimal downtime, provided the filesystem, orchestration, and the application itself support such changes, typically requiring less effort than resizing or adding virtual disks to traditional virtual machines.

Multiple disks can also be used as backups. Backup tools such as rsync or tar compression ensure rapid recovery while preserving data integrity. Volumes for simpler or low-traffic services can be backed up by creating tar archives that maintain permissions and ownership, especially for smaller solutions. Administrators can quickly switch disks by updating volume mappings with limited downtime.

Upgrading Containers

When upgrading software, companies can design their application data formats to be architecture-agnostic, so that new container images can reuse existing volumes across different platforms, making upgrades smoother. If problems occur after upgrading, as has already been discussed, it is simple to roll back to a previous image and restore the prior state.

These rapid rollback capabilities and isolated environments increase resilience against cyberattacks, protecting legacy systems that may suffer from infrequent patching or outdated dependencies.

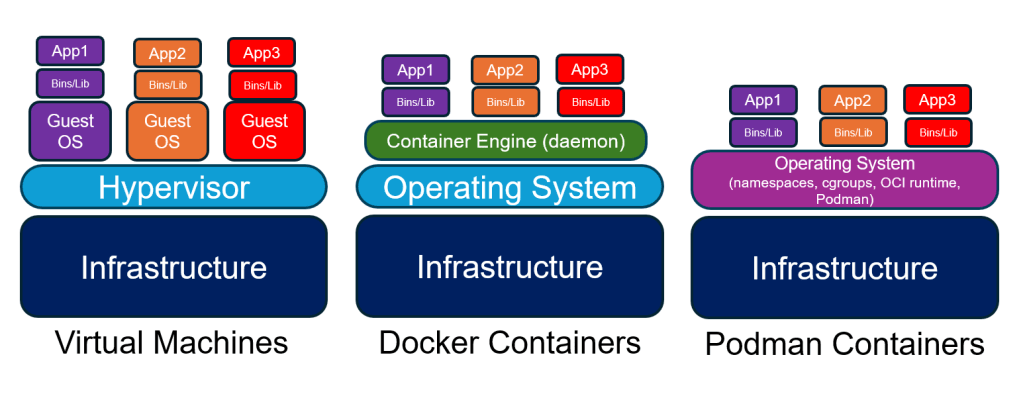

Containers vs. Virtual Machines: Resource Optimization and Attack Surface Reduction

Containers are often preferred over virtual machines because they are much lighter and more resource-efficient. While virtual machines run a full guest operating system, including a separate kernel, containers share the host’s kernel and package only the application and its userland dependencies. This results in significantly smaller disk usage, faster startup times, and easier scaling.

At the same time, containerized workloads frequently rely on more complex networking stacks, including CNI plugins, multiple network namespaces, and additional iptables or nftables rules, which can increase the potential attack surface if not carefully managed. In contrast, virtual machines provide a stronger isolation boundary through hardware virtualization and separate kernels, making them more resilient by default against certain classes of escape attacks.

Rollbacks and Business Continuity

Rollbacks on virtual machines can be slower and require more storage, as reverting typically involves entire system snapshots or multiple backups of the entire virtual machine. Separate data drives or single-service VMs can mitigate this but require additional configuration. Containers, on the other hand, isolate application layers and data volumes per component via layered filesystems, making backup and rollback inherently more efficient, which is critical for agile development and patch management.

Container Escape Risks & Core Mitigation

As containers share the host OS kernel, there is a potential risk called container escape, where a malicious exploit breaks isolation and gains access to the host system. Such exploits can arise from kernel vulnerabilities or misconfigurations. Unlike virtual machines with separate kernels, containers require layered mitigation measures such as SELinux, which are detailed later in this article.

Container runtimes use Linux security features like seccomp (restricting system calls), namespaces (isolating process and network views), and capabilities (limiting privileges). These layered controls help reduce attack surfaces and contain compromises within containers. Podman includes SELinux support by default, especially within the Red Hat ecosystem, which simplifies the process of configuring it.

Docker and Podman

Docker, which is the most widely used container solution, traditionally relies on a persistent, root-owned daemon that manages containers, creating a centralized attack surface that, if compromised, can lead to escalated privileges and lateral movement across containers. Although rootless Docker modes have been available for several years and Docker Desktop typically runs inside a virtual machine, most production deployments still use the traditional rootful Docker daemon model as the default configuration. In contrast, Podman was designed to support rootless operation and uses a daemonless model for container lifecycle management, running containers as regular user processes while delegating specific tasks to helper services such as Conmon (handles container process monitoring and logging), slirp4netns (provides user-mode networking in rootless mode), or fuse-overlayfs (enables rootless storage layers via FUSE) in rootless mode.

This removes a single, long‑running root daemon from the architecture and reduces the risk associated with a central point of failure, enhancing the overall security posture when properly configured.

Podman’s SELinux Integration

Podman has native integration with SELinux in distributions that support it by default, such as Red Hat Enterprise Linux and Fedora. SELinux is the mandatory access control system used in many enterprise Linux environments, with labels that actively enforce security policies, restricting what containers can access and do on the host system. This automated labeling and enforcement provides isolation and limits the impact of a compromised container.

SELinux enforces mandatory access control (MAC) policies that restrict how processes and objects (files, sockets, etc.) interact on a system. Every process and object is assigned a security context, expressed as a label with multiple fields such as user, role, type, and level. These labels determine what actions are allowed or denied by the kernel.

Podman containers run processes with a specific SELinux context, typically labeled as container_t or container_runtime_t. Additionally, Podman applies unique MCS (Multi-Category Security) labels to each container instance, effectively isolating them from each other even though they share the same host kernel. This fine-grained labeling limits containers’ access to only the resources explicitly permitted by policy.

SELinux also uses Multi-Category Security (MCS) labels to provide fine-grained per-container isolation. Each container receives a unique MCS label, which limits its access to only the resources explicitly allowed by policy, preventing containers from interfering with each other or the host. This strong mandatory access control reduces risks of lateral movement and containment breaches.

This approach contrasts with traditional discretionary access control (DAC) mechanisms (like Unix file permissions), which rely on user IDs and can be bypassed if a process has elevated rights.

Docker also supports SELinux but often requires manual configuration to enable the correct labeling and enforcement modes. Podman’s default behavior ensures containers are always run with appropriate SELinux labels and context, making it a safer default for secure container deployments, especially on systems where SELinux is enabled and enforced. In YAML files, appending :Z to volume configurations applies a private SELinux label for that container, while :z applies a shared label so multiple containers can access the same volume safely, making them SELinux-compatible and ready for use.

The SELinux-based isolation described above applies only on systems where SELinux is installed, enabled, and enforcing, such as typical RHEL or Fedora. On distributions without SELinux implemented, Podman does not provide SELinux labeling, but it still uses Linux user namespaces to isolate containers.

Extra Layer: Rootless User Namespaces

Beyond just running rootless and using SELinux, Podman also makes use of Linux user namespaces to add an extra layer of security. What this means is that the user IDs inside the container get mapped to different, unprivileged user IDs on the host system. Therefore, if an attacker manages to escape from a container, the attacker does not gain elevated privileges on the host system by default.

What Are OCI Standards and Why They Matter

The Open Container Initiative (OCI) defines open standards for container images and runtimes, ensuring interoperability. Podman’s compliance with OCI standards means containers are portable across compliant platforms, follow security best practices, and avoid vendor lock-in. This standardization promotes a secure ecosystem with predictable behavior and reduced complexity.

As a result, most container images designed for Docker can run seamlessly on Podman, often without requiring root permissions.

Podman: A Daemonless, Rootless Container Engine with Security-First Design

Podman is a container runtime adhering to OCI (Open Container Initiative) standards, distinguished by its daemonless architecture and ability to operate without root privileges. Unlike Docker, which relies on a persistent root-level daemon that can become a single point of compromise, Podman avoids this security vulnerability by running containers as independent processes.

Networking in Podman and Packet Capture Capabilities

Podman creates isolated virtual networks for containers by default, segmenting container traffic from the host and other containers to enhance security. Containers communicate through configured network interfaces and bridges, which are separate from the host’s main network stack. Packet capture tools running inside a container or on the host can only capture traffic that passes through their respective network interfaces and to which they have access.

Since Podman’s rootless containers operate with unprivileged user namespaces and isolated networks, conducting packet sniffing requires explicit network setup and elevated privileges.

To capture packets within a container using tools like tcpdump, the container must be run as a rootful container, as it happens with Docker, with added capabilities such as –cap-add=NET_ADMIN and –cap-add=NET_RAW. Alternatively, running the container as rootful with the –network=host option gives it full access to the host’s network stack, enabling packet capture but reducing network isolation. Use of the –privileged flag further grants permissions necessary for packet sniffing but increases the container’s attack surface.

Due to these restrictions, packet sniffing inside rootless Podman containers without elevated privileges is generally not feasible, which aligns with Podman’s goal to minimize privilege exposure and limit unauthorized network monitoring from within containers. This design supports protecting network traffic confidentiality and reduces the risk of lateral movement via network monitoring from compromised containers.

Using Podman: Syntax and Commands

As Podman follows OCI standards and offers a command-line interface that closely mirrors Docker’s syntax, adoption of Podman as a secure container runtime is achievable without a steep learning curve.

Installation on major Linux distributions via package managers, for example for Debian-based distributions:

#Install podman in Debian/Ubuntu/

sudo apt install podman

#Launching containers in detached mode:

podman run -dt --name my_container nginx

#Monitoring active containers:

podman ps

#Accessing container shells:

podman exec -it my_container /bin/bash

#Stopping a container

podman stop my_container

#Removing a container

podman rm my_container

#Port mapping to expose services while maintaining default isolation:

podman run -d -p 8080:80 --name httpd-basic quay.io/httpd-parentDocker Compose is a tool for defining and running multi-container Docker applications using a single YAML file. Multi-container orchestration is supported via Podman Compose, a drop-in replacement for Docker Compose.

To install Podman Compose, you need Python 3 and pip installed on your system.

Then you can install Podman Compose using pip:

#Install python3 and pip

sudo apt install python3 python3-pip

#Install podman compose

pip3 install podman-compose

#Deploy a Podman Compose:

podman-compose up -dBy default, Podman rootless containers are isolated from external networks, minimizing unnecessary attack vectors unless explicit exposure is configured.

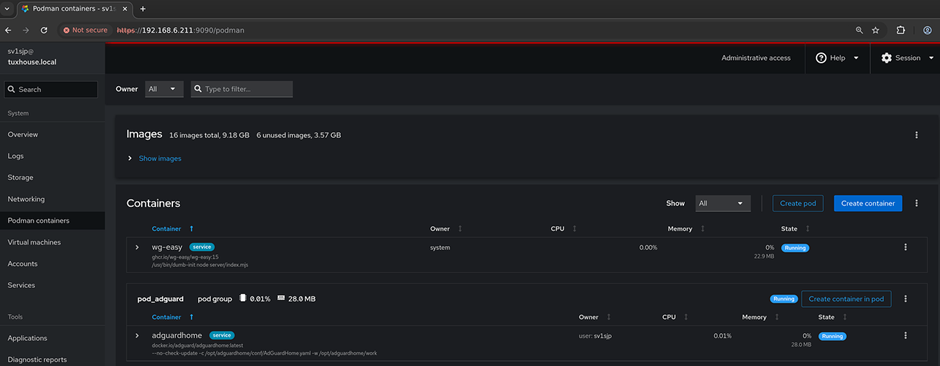

Combined with graphical tools such as Podman Desktop application and enterprise interfaces such as Cockpit, Podman equips security teams with flexible, secure container management options without sacrificing operational familiarity.

Podman and Kubernetes Integration

Podman Compose is well-suited for managing multi-container applications locally, and Podman also integrates effectively with larger orchestration platforms such as Kubernetes.

As Podman follows OCI standards, containers built with Podman can be exported as YAML files in order to be deployed into Kubernetes clusters to help teams export their local setups into cluster-ready manifests, contributing to a smooth transition from local development to production environments that require more scalable solutions.

Instead of acting as a Kubernetes node agent, Podman focuses on emulating the Kubernetes pod model on a single host and provides a compatible runtime and tooling layer that mirrors how workloads are structured in Kubernetes, so that the same images and pod definitions can later be orchestrated by a full Kubernetes cluster.

Managing Podman Containers with Graphical Interfaces

In addition to regular command-line interaction with podman, Podman integrates seamlessly with graphical tools for easier container management.

Cockpit, for example, is a web-based admin interface built into Red Hat Enterprise Linux, though it can be installed on other distributions as well and it supports direct management of Podman containers.

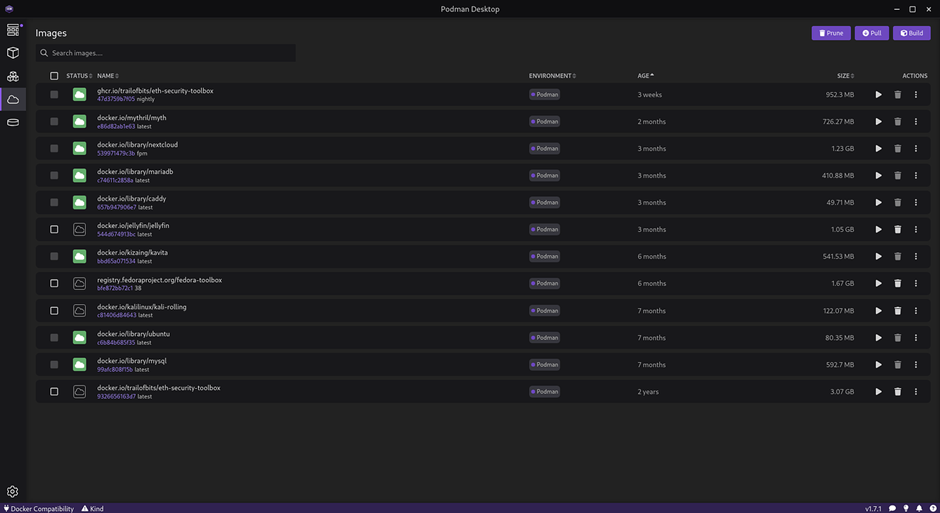

Podman Desktop, on the other hand, is an application that enables users to manage containers intuitively from a desktop application.

Conclusion

Podman provides a secure, efficient, and flexible container runtime that aligns well with modern cybersecurity requirements. Its rootless and daemonless design strengthens security by reducing the number of privileged components and shrinking the attack surface. With fast deployments, easy rollback options, and smooth integration into existing enterprise environments, Podman is a strong alternative for security-focused companies looking for a daemonless and rootless container solution.

For further details and official guidance, visit the Podman documentation at: https://docs.podman.io

Dimitris Vagiakakos

Dimitris Vagiakakos (sv1sjp) is a Cybersecurity Consultant and Penetration Tester at NVISO Security, and host of Linux-User.gr, the Hellenic Linux Community. As a Linux user from the age of 5, he has a deep understanding of cybersecurity across Infrastructure, Business, and Blockchain/Web3 ecosystems. Dimitris also has a passion for creating educational content supporting newer generations in Computer Science and cybersecurity awareness.

It’s pretty great, and I like that the workflow for creating containers is sliiiightly easier than on Docker. I switched from Docker to Podman for most stuff about a year ago and so far there are only two hiccups that I lament:

* the higher disk consumption due to not being able to share image storage. (I’ve tried with “additionalstorages“ but that seems to only be respected for podman run; podman build and podman compose seem to ignore it and *always* pull images from the registries)

* Some annoying isses with fule permissions due to rootless design – running rootless containers will create files under your *user storage* that you as a user have no permission to transfer or remove for cleanup or security, and *severely* breaks the output of tools like “du“ or “find“ due to error spammage.