This week I try to figure out “what makes a driver a driver?” and experiment with writing my own kernel hooks.

1. Windows Kernel Programming 101

In the first part of this internship blog series, we took a look at how EDRs interact with User and Kernel space, and explored a frequently used feature called Kernel Callbacks by leveraging the Windows Kernel Ps Callback Experiments project by @fdiskyou to patch them in memory. Kernel callbacks are only the first step in a line of defense that modern EDR and AV solutions leverage when deploying kernel drivers to identify malicious activity. To better understand what we’re up against, we need to take a step back and familiarize ourselves with the concept of a driver itself.

To do just that, I spent the vast majority of my time this week reading the fantastic book Windows Kernel Programming by Pavel Yosifovich, which is a great introduction to the Windows kernel and its components and mechanisms, as well as drivers and their anatomy and functions.

In this blogpost I would like to take a closer look at the anatomy of a driver and experiment with a different technique called IRP MajorFunction hooking.

2. Anatomy of a driver

Most of us are familiar with the classic C/C++ projects and their characteristics; for example, the int main(int argc, char* argv[]){ return 0; } function, which is the typical entry point of a C++ console application. So, what makes a driver a driver?

Just like a C++ console application, a driver requires an entry point as well. This entry point comes in the form of a DriverEntry() function with the prototype:

NTSTATUS DriverEntry(_In_ PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject, _In_ PUNICODE_STRING RegistryPath);

The DriverEntry() function is responsible for 2 major tasks:

- setting up the driver’s

DeviceObjectand associated symbolic link - setting up the dispatch routines

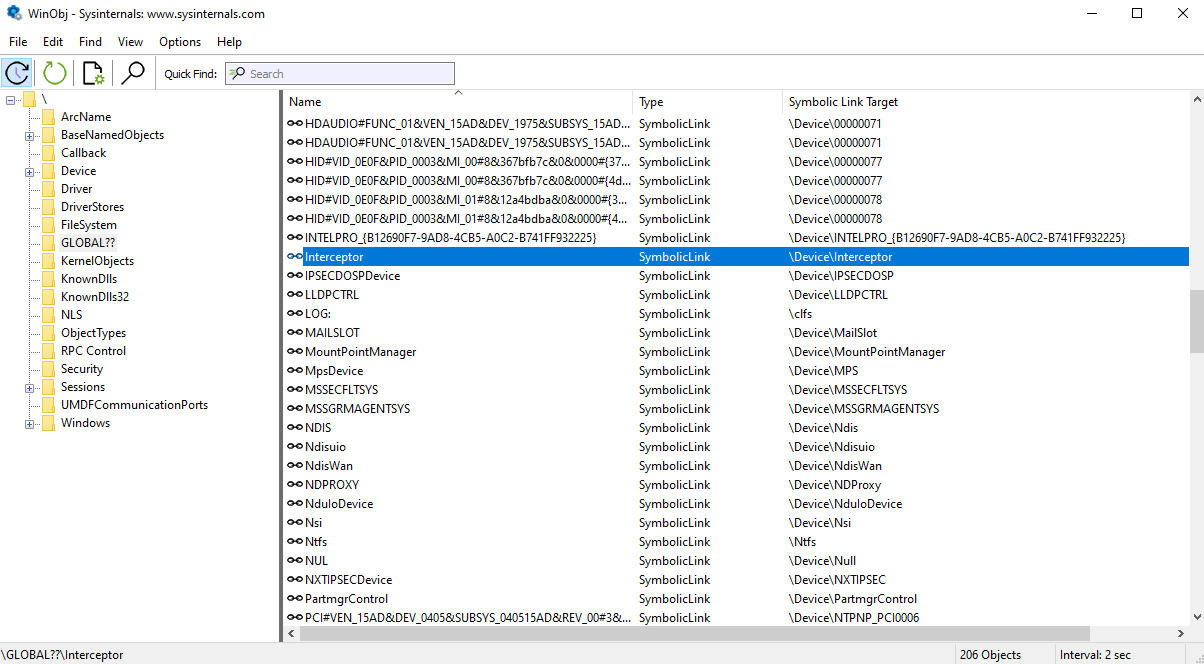

Every driver needs an “endpoint” that other applications can use to communicate with. This comes in the form of a DeviceObject, an instance of the DEVICE_OBJECT structure. The DeviceObject is abstracted in the form of a symbolic link and registered in the Object Manager’s GLOBAL?? directory (use sysinternal’s WinObj tool to view the Object Manager). User mode applications can use functions like NtCreateFile with the symbolic link as a handle to talk to the driver.

Example of a C++ application using CreateFile to talk to a driver registered as “Interceptor” (hint: it’s my driver 😉 ):

HANDLE hDevice = CreateFile(L"\\\\.\\Interceptor)", GENERIC_WRITE | GENERIC_READ, 0, nullptr, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, nullptr);

Once the driver’s endpoint is configured, the DriverEntry() function needs to sort out what to do with incoming communications from user mode and other operations such as unloading itself. To do this, it uses the DriverObject to register Dispatch Routines, or functions associated with a particular driver operation.

The DriverObject contains an array, holding function pointers, called the MajorFunction array. This array determines which particular operations are supported by the driver, such as Create, Read, Write, etc. The index of the MajorFunction array is controlled by Major Function codes, defined by their IRP_MJ_ prefix.

There are 3 main Major Function codes along side the DriverUnload operation which need initializing for the driver to function properly:

// prototypes

void InterceptUnload(PDRIVER_OBJECT);

NTSTATUS InterceptCreateClose(PDEVICE_OBJECT, PIRP);

NTSTATUS InterceptDeviceControl(PDEVICE_OBJECT, PIRP);

//DriverEntry

extern "C" NTSTATUS

DriverEntry(PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject, PUNICODE_STRING RegistryPath) {

DriverObject->DriverUnload = InterceptUnload;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_CREATE] = InterceptCreateClose;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_CLOSE] = InterceptCreateClose;

DriverObject->MajorFunction[IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL] = InterceptDeviceControl;

//...

}

The DriverObject->DriverUnload dispatch routine is responsible for cleaning up and preventing any memory leaks before the driver unloads. A leak in the kernel will persist until the machine is rebooted. The IRP_MJ_CREATE and IRP_MJ_CLOSE Major Functions handle CreateFile() and CloseHandle() calls. Without them, handles to the driver wouldn’t be able to be created or destroyed, so in a way the driver would be unusable. Finally, the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL Major Function is in charge of I/O operations/communications.

A typical driver communicates by receiving requests, handling those requests or forwarding them to the appropriate device in the device stack (out of scope for this blogpost). These requests come in the form of an I/O Request Packet or IRP, which is a semi-documented structure, accompanied by one or more IO_STACK_LOCATION structures, located in memory directly following the IRP. Each IO_STACK_LOCATION is related to a device in the device stack and the driver can call the IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation() function to retrieve the IO_STACK_LOCATION related to itself.

The previously mentioned dispatch routines determine how these IRPs are handled by the driver. We are interested in the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL dispatch routine, which corresponds to the DeviceIoControl() call from user mode or ZwDeviceIoControlFile() call from kernel mode. An IRP request destined for IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL contains two user buffers, one for reading and one for writing, as well as a control code indicated by the IOCTL_ prefix. These control codes are defined by the driver developer and indicate the supported actions.

Control codes are built using the CTL_CODE macro, defined as:

#define CTL_CODE(DeviceType, Function, Method, Access)((DeviceType) << 16 | ((Access) << 14) | ((Function) << 2) | (Method))

Example for my Interceptor driver:

#define IOCTL_INTERCEPTOR_HOOK_DRIVER CTL_CODE(0x8000, 0x800, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

#define IOCTL_INTERCEPTOR_UNHOOK_DRIVER CTL_CODE(0x8000, 0x801, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

#define IOCTL_INTERCEPTOR_LIST_DRIVERS CTL_CODE(0x8000, 0x802, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

#define IOCTL_INTERCEPTOR_UNHOOK_ALL_DRIVERS CTL_CODE(0x8000, 0x803, METHOD_BUFFERED, FILE_ANY_ACCESS)

3. Kernel land hooks

Now that we have a vague idea how drivers communicate with other drivers and applications, we can think about ways to intercept those communications. One of these techniques is called IRP MajorFunction hooking.

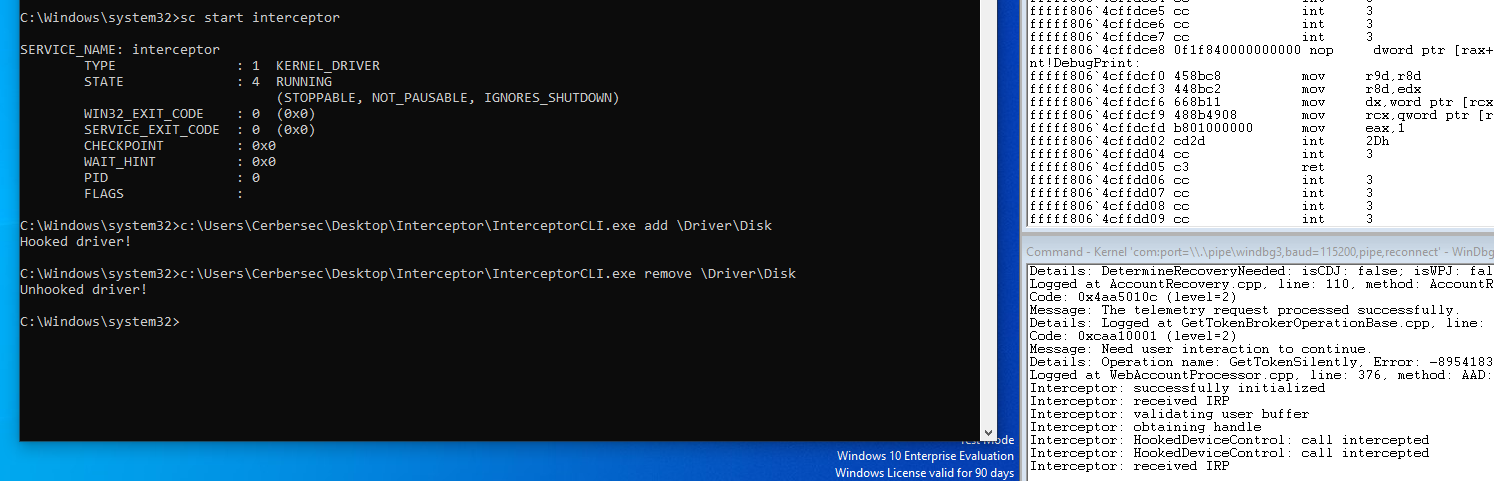

Since drivers and all other kernel processes share the same memory, we can also access and overwrite that memory as long as we don’t upset PatchGuard by modifying critical structures. I wrote a driver called Interceptor, which does exactly that. It locates the target driver’s DriverObject and retrieves its MajorFunction array (MFA). This is done using the undocumented ObReferenceObjectByName() function, which uses the driver device name to get a pointer to the DriverObject.

UNICODE_STRING targetDriverName = RTL_CONSTANT_STRING(L"\\Driver\\Disk");

PDRIVER_OBJECT DriverObject = nullptr;

status = ObReferenceObjectByName(

&targetDriverName,

OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE,

nullptr,

0,

*IoDriverObjectType,

KernelMode,

nullptr,

(PVOID*)&DriverObject

);

if (!NT_SUCCESS(status)) {

KdPrint((DRIVER_PREFIX "failed to obtain DriverObject (0x%08X)\n", status));

return status;

}

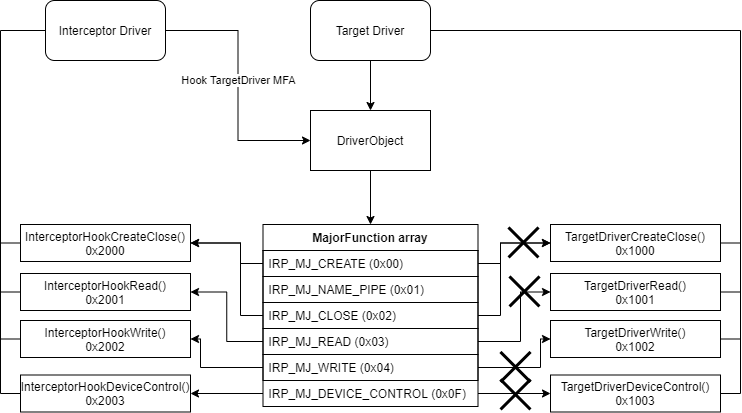

Once it has obtained the MFA, it will iterate over all the Dispatch Routines (IRP_MJ_) and replace the pointers, which are pointing to the target driver’s functions (0x1000 – 0x1003), with my own pointers, pointing to the *InterceptHook functions (0x2000 – 0x2003), controlled by the Interceptor driver.

for (int i = 0; i < IRP_MJ_MAXIMUM_FUNCTION; i++) {

//save the original pointer in case we need to restore it later

globals.originalDispatchFunctionArray[i] = DriverObject->MajorFunction[i];

//replace the pointer with our own pointer

DriverObject->MajorFunction[i] = &GenericHook;

}

//cleanup

ObDereferenceObject(DriverObject);

As an example, I hooked the disk driver’s IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL dispatch routine and intercepted the calls:

This method can be used to intercept communications to any driver but is fairly easy to detect. A driver controlled by EDR/AV could iterate over its own MajorFunction array and check the function pointer’s address to see if it is located in its own address range. If the function pointer is located outside its own address range, that means the dispatch routine was hooked.

4. Conclusion

To defeat EDRs in kernel space, it is important to know what goes on at the core, namely the driver. In this blogpost we examined the anatomy of a driver, its functions, and their main responsibilities. We established that a driver needs to communicate with other drivers and applications in user space, which it does via dispatch routines registered in the driver’s MajorFunction array.

We then briefly looked at how we can intercept these communications by using a technique called IRP MajorFunction hooking, which patches the target driver’s dispatch routines in memory with pointers to our own functions, so we can inspect or redirect traffic.

About the authors

Sander (@cerbersec), the main author of this post, is a cyber security student with a passion for red teaming and malware development. He’s a two-time intern at NVISO and a future NVISO bird.

Jonas is NVISO’s red team lead and thus involved in all red team exercises, either from a project management perspective (non-technical), for the execution of fieldwork (technical), or a combination of both. You can find Jonas on LinkedIn.

One thought on “Kernel Karnage – Part 2 (Back to Basics)”